title: Calbirating Trust —

Typically robot policies are found to comply and supplement human preferences. This is sufficient for most cases of human-robot interation (HRI) since the human is genrally considered to be a good maximizers of task rewards. However, what happens when the human is behaving suboptimally according the the robot’s reward function? In these cases there are several questions that the must be adressed when interecting:

- Should the robot intervene to mitigate the effect of suboptimal behavior in team performance?

- Should the robot comply with the human to preserve their relationship (trust) and improve future team performance?

- Is the human truely suboptimal or do they just look that way to the robot’s assumed reward and limited generalizability?

Mutual Adaptation

One approach to the answering the first two questions is to balance a tradeoff between team performance and preserved trust based on the adaptability of the human. The following studies look at how we can approach interacting with humans that behave unexpectedly according to the robot’s reward function.

Sample Projects

In a collaborative table carrying task (found here), the authors assigned the human goal, either being the first or second agent to pass through the door, to be inherantly suboptimal no matter their actual choice. This is done under the assumption that the human will make decisions with incomplete information about the dynamics of the robot. For example, the sensing capabilities may be better on a certain side of the robot and make a given order of agents through the door optimal. However, if the a robot were to insist on a conflicting goal with a stubborn human, then the robot’s reward would increase but conflicts that degrade trust would be generated. Conversely, if the human is more tollerant of intervention, then the robot can increase team performance with minimal degradation of trust. They found that the robot was able to achieve higher rewards under a mutaully-adaptive mode of behavior when compared to the traditional one-way adaptation (the robot follows human preferences in all cases). Also, they found that there was little significant difference in trust between these to models. Therefore, this shows that there is an opportunity to increase team performance while preserving trust by estimating how adaptable the human is and incorperating into the robot’s decision-making.

Similar studies were done with table-carrying (found here) and table-clearing (found here) that applied this same mutual-adapation model and found similar results. The latter table-clearing study is the likely the most useful due to the higher resolution of the action space and applicability of the algorithm to other domains.

Additional Reading

- Human-robot mutual adaptation in collaborative tasks: Models and experiments

- Formalizing human-robot mutual adaptation: A bounded memory model

- Human-Robot Mutual Adaptation in Shared Autonomy

Incorperating Unexpected Human Behaviors

The previous section deals with how to interact with humans that are suboptimal. We will now look at how to calibrate trust when the human is not necesarrly behaving subotionally or when there is low ammount of trust in the robot. Humans tend to be very good at make decisions in new scenarios. Robots are not so good at this and can percieve the human to be acting suboptimally when infact they are not. This also motivates a second question; does the human even want the help of the robot? The following studies will look at these perspectives and provide a framework of dealing with unexpected behaviors.

Sample Projects

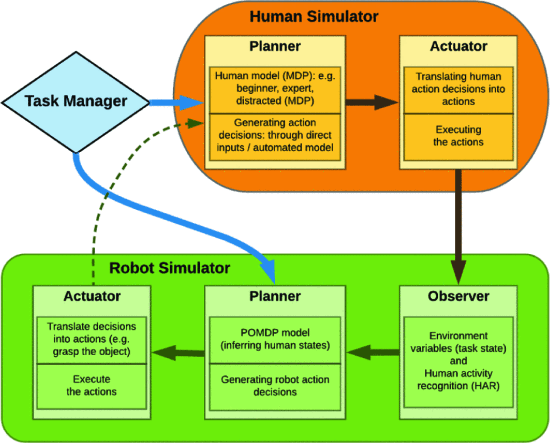

The authors in social cobot paper (found here proposed a way that the human may a) have intentions that are irrelevant and unkown intentions (motivation loss, alternative tasks, fatigue, ect…) and b) relevant intentions that they do not want the robot to assist with (distrust in robot, emotional state, ect…). They generated robot behavior that can both actively assist, stand by until needed, or communicate unexpected behaviors in a way that aligns with their turst in the robot. Consequently, the robot optimally achieves the collaboration without overstepping its role in the human’s task. The best example of this would be when the human does not desire robot intervention (due to distrust) but is distracted (looking around or performing tasks irrelevant to team goals), the robot may point to the object that it thinks is the optimal action that the human should take. They foound that proactively planning robot behavior, in accordance with the estimated trust in the robot, generated the most successfull interaction.

A similar study was done (found here) where humans and robots intermittantly collaborated on a factory floor. These authors were able to identify human states and intentions to effictively collaborate in, take-over, and surrender tasks as the human moved around this enviorment under thier proposed models of trust.